Printing, or the process of reproducing text and images, has a long history behind it. This page describes the evolution of print. It acts as a summary of a more elaborate description which starts

here. You can also click on the title of each century to get more in-depth information. There is a separate section on the

history of prepress.

3000 BC and earlier

The Mesopotamians use round cylinder seals for rolling an impress of images onto clay tablets. In other early societies in China and Egypt, small stamps are used to print on cloth.

Second century AD

A Chinese man named Ts’ai Lun is credited with inventing paper.

Seventh century

A small book containing the text of the Gospel of John in Latin is added to the grave of Saint Cuthbert. In 1104 it is recovered from his coffin in Durham Cathedral, Britain. The Cuthbert Gospel is currently the oldest European book still in existence.

Eleventh century

A Chinese man named Pi-Sheng develops type characters from hardened clay, creating the first movable type. The fairly soft material hampers the success of this technology.

Twelfth century

Papermaking reaches Europe.

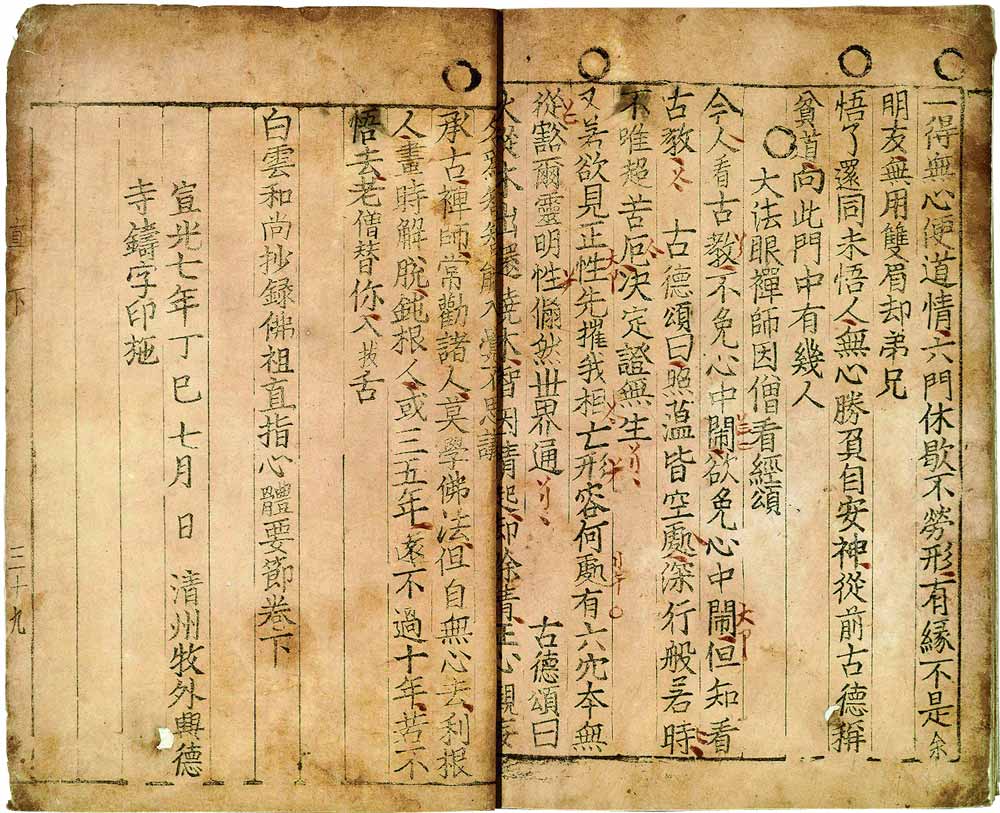

Thirteenth century

Type characters cast from metal (bronze) are developed in China, Japan and Korea. The oldest known book printed using metal type dates back to the year 1377. It is a Korean Buddhist document, called Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Seon Masters.

Even though woodcut had already been in use for centuries in China and Japan, the oldest known European specimen dates from the beginning of the 15th century. Woodcut is a relief printing technique in which text and images are carved into the surface of a block of wood. The printing parts remain level with the surface while the non-printing parts are removed, typically with a knife or chisel. The wood block is then inked and the substrate pressed against the wood block. The ink that is used is made of lampblack (soot from oil lamps) mixed with varnish or boiled linseed oil.

Books are still rare since they need to be laboriously handwritten by scribes. The University of Cambridge has one of the largest libraries in Europe – constituting of just 122 books.

In 1436 Gutenberg begins work on a printing press. It takes him 4 years to finish his wooden press which uses movable metal type. Among his first publications that get printed on the new device are bibles. The first edition has 40 lines per page. A later 42-line version comes in two volumes.

In 1465 the first drypoint engravings are created by the Housebook Master, a south German artist. Drypoint is a technique in which an image is incised into a (copper) plate with a hard-pointed ‘needle’ of sharp metal or a diamond point.

In their print shop in Venice John and Wendelin of Speier are probably the first printers to use pure roman type, which no longer looks like the handwritten characters that other printers have been trying to imitate until then.

In 1476 William Caxton buys equipment from the Netherlands and establishes the first printing press in England at Westminster. The painting below depicts Caxton showing his printing press to King Edward IV.

That same year

copper engravings are for the first time used for illustrations. With engravings, a drawing is made on a copper plate by cutting grooves into it.

By the end of the century, printing has become established in more than 250 cities around Europe. One of the main challenges of the industry is distribution, which leads to the establishment of numerous book fairs. The most important one is the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Aldus Manutius is the first printer to come up with smaller, more portable books. He is also the first to use Italic type, designed by Venetian punchcutter Francesco Griffo.

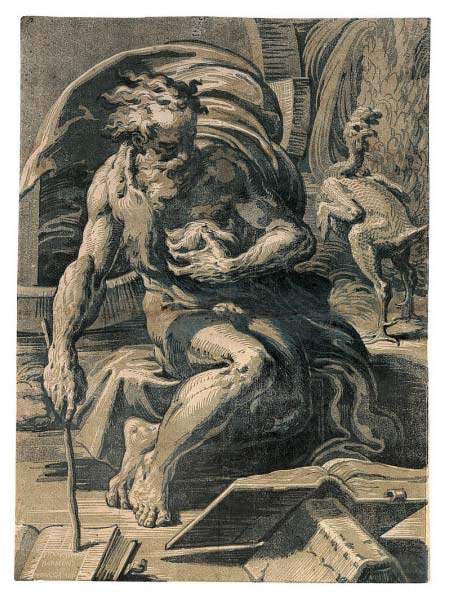

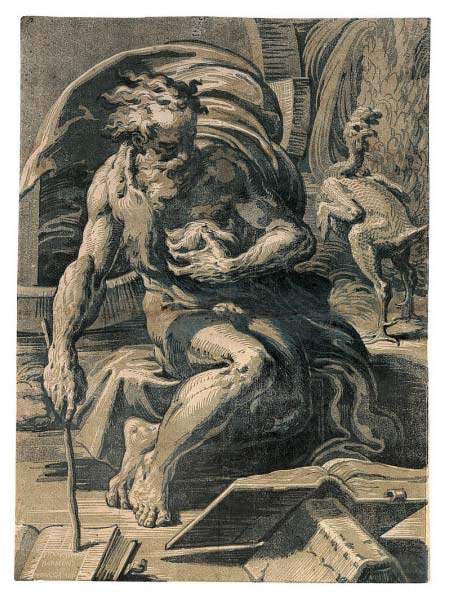

In 1507 Lucas Cranach invents the chiaroscuro woodcut, a technique in which drawings are reproduced using two or more blocks printed in different colors. The Italian Ugo da Carpi is one of the printers to use such woodcuts, for example in Diogenes, the work shown below.

In 1525 the famous painter, wood carver and copper engraver

Albrecht Dürerpublishes

‘Unterweysung der Messung’ (A Course on the Art of Measurement), a book on the geometry of letters.

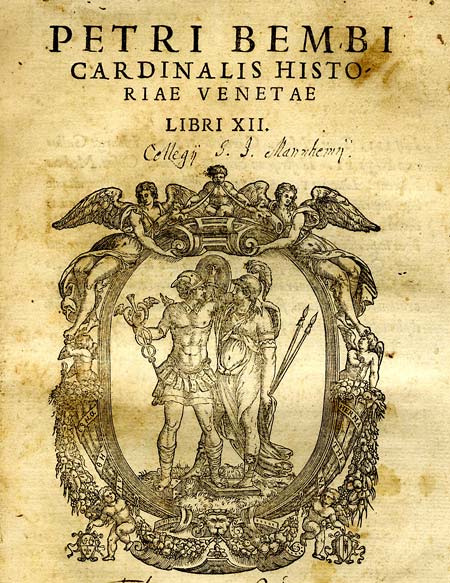

The ‘Historia Veneta’ (1551) is one of the many books of Pietro Bembo, a Venetian scholar and cardinal who is most famous for his work on the Italian language and poetry. The Bembo typeface is named after him.

Christophe Plantin is one of the most famous printers of this century. In his print shop in Antwerp, he produces fine work ornamented with engravings after Rubens and other artists. Many of his works as well as some of the equipment from the shop can be admired in the

Plantin-Moretus museum.

Plantin is also the first to print a facsimile. A facsimile is a reproduction of an old book, manuscript, map, art print or other item that is as true to the original source as possible.

The word ‘not’ is accidentally left out of Exodus 20:14 in a 1631 reprint of the King James Bible. The Archbishop of Canterbury and King Charles I are not amused when they learn that God commanded Moses “Thou shalt commit adultery”. The printers, Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, are fined and have their printing license revoked. This version of the Bible is referred to as The Wicked Bible and also called the Adulterous Bible or Sinner’s Bible.

In Paris, the Imprimerie Royale du Louvre is established in 1640 at the instigation of Richelieu. The first book that is published is ‘De Imitatione Christi’ (The Imitation of Christ), a widely read Catholic Christian spiritual book that was first published in Latin around 1418.

In 1642 Ludwig von Siegen invents mezzotint, a technique to reproduce halftones by roughening a copper plate with thousands of little dots made by a metal tool with small teeth, called a ‘rocker’. The tiny pits in the plate hold the ink when the face of the plate is wiped clean.

The first American paper mill is established in 1690.

In 1710 the German painter and engraver Jakob Christof Le Blon produces the first engraving in several colors. He uses the mezzotint method to engrave three metal plates. Each plate is inked with a different color, using red, yellow and blue. Later on, he adds a fourth plate, bearing black lines. This technique helped form the foundation for modern color printing. Le Bon’s work is based on Newton’s theory, published in 1702, which states that all colors in the spectrum are composed of the three primary colors blue, yellow and red.

William Caslon is an English typographer whose foundry operates in London for over 200 years. His Caslon Roman Old Face is cut between 1716 and 1728. The letters are modeled on Dutch types but they are more delicate and not as monotonous. Caslon’s typefaces remain popular, digital versions are still available today.

The

Gentleman’s Magazine is published for the first time in 1731. It is generally considered to be the first general interest magazine. The publication runs uninterrupted until 1922.

In 1732 Benjamin Franklin establishes his own printing office and becomes the publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Among his publications Poor Richard’s Almanac becomes the most famous.

Alois Senefelder invents lithography in 1796 and uses it as a low-cost method for printing theatrical works. In a more refined form lithography is still the dominant printing technique today.

Another famous person from this era is Giambattista Bodoni who creates a series of typefaces that carry his name and that are still frequently used today. They are characterized by the sharp contrast between the thick vertical stems and thin horizontal hairlines.

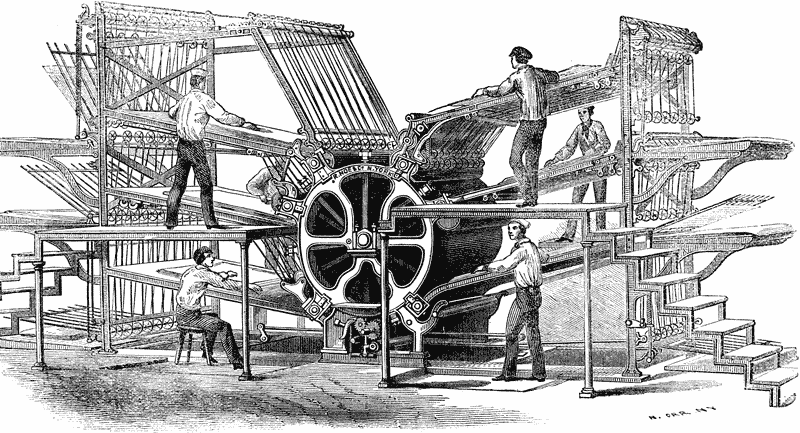

In 1800 Charles Stanhope, the third Earl Stanhope, builds the first press which has an iron frame instead of a wooden one. This Stanhope press is faster, more durable and it can print larger sheets. A few years later another performance improvement is achieved by Friedrich Gottlob Koenig and Andreas Friedrich Bauer who build their first cylinder press. Their company is still in existence today and is known as KBA.

In 1837 Godefroy Engelmann is awarded a patent on

chromolithography, a method for printing in color using lithography. Chromolithographs or chromos are mainly used to reproduce paintings. The advertisement below is from the end of the century and shows what can be achieved using this color printing technique. Another popular technique is the photochrom process, which is mainly used to print

postcards of landscapes.

The Illustrated London News is the world’s first illustrated weekly newspaper. It costs five pence in 1842. A year later Sir Henry Cole commissions the English painter John Callcott Horsley to do the artwork of (arguably) the first commercial Christmas card. Around 1000 cards are printed and hand-colored. Ten of these are still in existence today.

Around the same time the American inventor Richard March Hoe builds the first lithographic rotary printing press, a press in which the type is placed on a revolving cylinder instead of a flatbed. This speeds up the printing process considerably.

The Czech painter Karel Klíč invents photogravure in 1878. This process can be used to faithfully reproduce the detail and continuous tones of photographs.

In typesetting Ottmar Mergenthaler’s 1886 invention of the Linotype composing machine is a major step forward. With this typesetter, an operator can enter text using a 90-character keyboard. The machine outputs the text as slugs, which are lines of metal type.

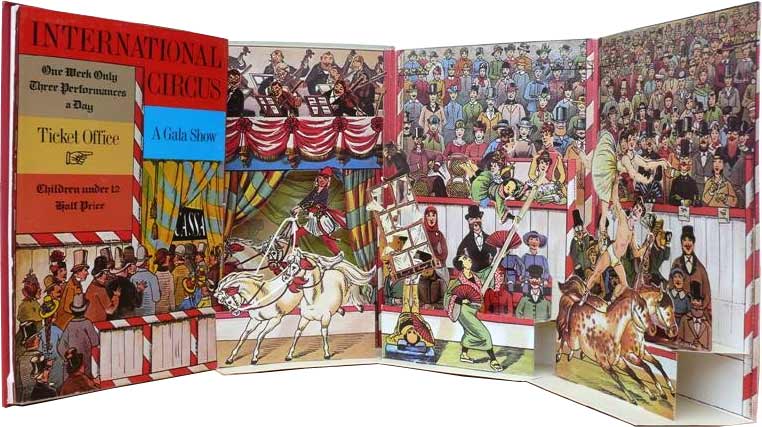

Lothar Meggendorfer’s International Circus is a nice example of the quality that could be achieved in those days. This pop-up book contains six pop-up scenes of circus acts, including acrobats, clowns, and daredevil riders.

In 1890 Bibby, Baron and Sons build the first flexographic press. This type of press uses the relief on a rubber printing plate to hold the image that needs to be printed. Because the ink that is used in that first flexo press smears easily, the device becomes known as Bibby’s Folly.

In 1903 American printer Ira Washington Rubel is instrumental in producing the first lithographic offset press for paper. In offset presses a rubber roller transfers the image from a printing plate or stone to the substrate. Such an offset cylinder was already in use for printing on metals, such as tin.

In 1907 the Englishman Samuel Simon is awarded a patent for the process of using silk fabric as a printing screen. Screen printing quickly becomes popular for producing expensive wallpaper and printing on fabrics such as linen and silk. Screen printing had first appeared in China during the Shang Dynasty (960–1279 AD).

A few of the new press manufacturers that appear on the market are Roland(nowadays known as Man Roland) in 1911 and Komori Machine Works in 1923.

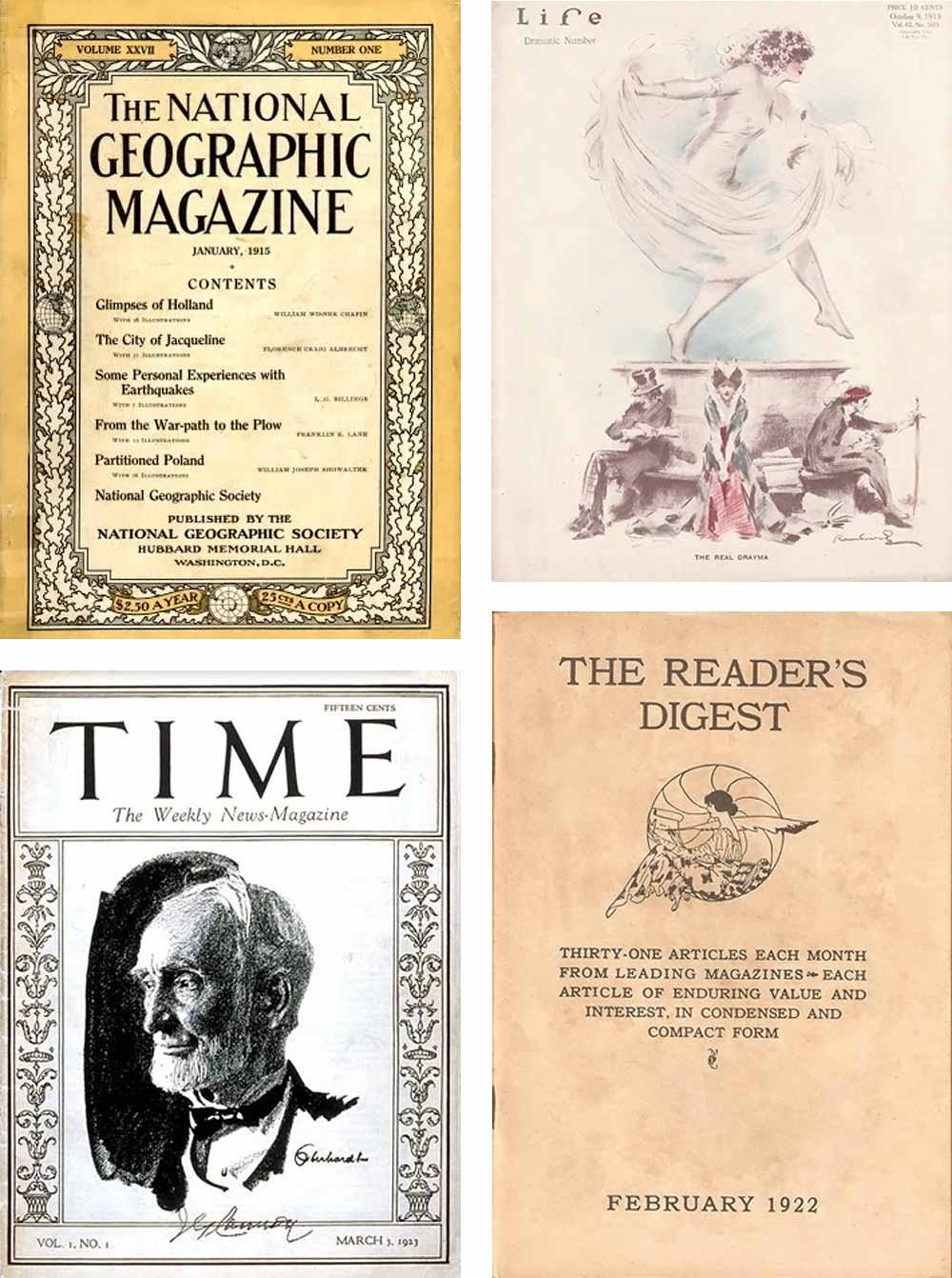

In 1915 Hallmark, founded in 1910, creates its first Christmas card. It is during this same era that magazines such as the National Geographic Magazine (1888), Life (1883, but focussing on photojournalism from 1936), Time (1923), Vogue (1892) and The Reader’s Digest (1920) starting reaching millions of readers.

Press manufacturer Koenig & Bauer launch the four-color Iris printing press in 1923. It can be used for printing banknotes. Over time security printing becomes one of the main focus points of the company.

The first commercially successful series of paperback books is published by Penguin Books in the UK in 1935. Earlier in 1931 German publisher Albatross Books had already tried to market a series of lower-priced books with a paper cover and glue binding. Penguin copied many of the concepts of their failed attempt, such as the use of color-coded covers.

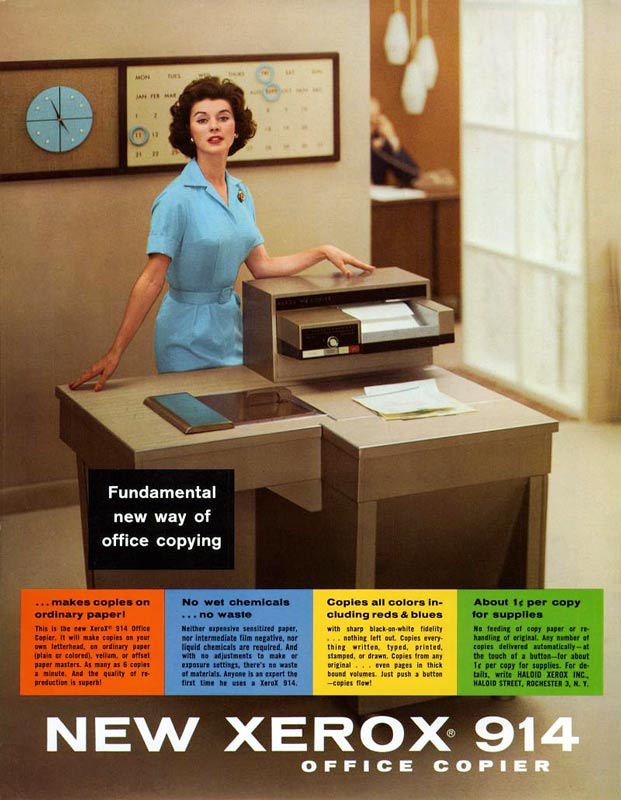

In 1938 Xerography, a dry photocopying technique is invented by Chester Carlson. The first commercial xerographic copier is introduced in 1949 but it is the 1959 Xerox 914 plain paper copier that is the breakthrough.

Japanese machine tool manufacturer Shinohara Machinery Company begins manufacturing flatbed letterpress machines in 1948. A popular press from that time is the Heidelberg Tiegel. The picture below shows it being demonstrated to German finance minister Ludwig Erhard at the first drupa trade show in 1951.

In 1967 the ISBN or International Standard Book Number started. This is a unique numeric identifier for commercial books. That same year Océ enters the office printing market with an electro-photographic process for copying documents using a special chemically-treated type of paper.

New materials like silicone make it possible for manufacturers such as Tampoprint to build more efficient presses for printing on curved surfaces. Pad printing can now be done on an industrial scale.

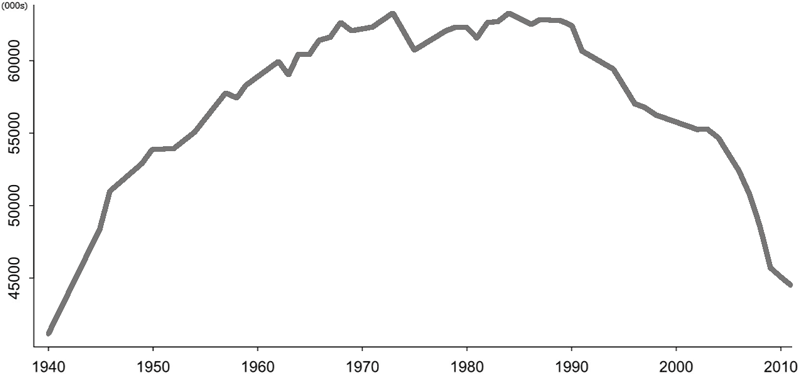

In the USA newspaper circulation reaches its highest level ever in 1973. It will remain fairly steady until a gradual decline sets in during the mid-’80s.

The first laser printers, such as the IBM 3800 and Xerox 9700, hit the market in 1975. They are prohibitively expensive but useful for applications such as cheque printing.

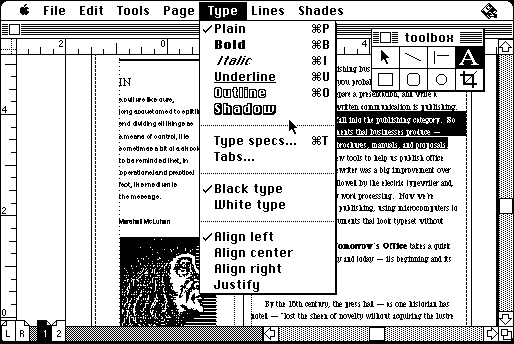

Desktop publishing takes off in 1985. The combination of the Apple Macintosh computer, printers and imagesetters powered by Adobe PostScript and the layout application Aldus PageMaker makes publishing more affordable.

At drupa 1986 MAN Roland Druckmaschinen AG introduces its LITHOMANcommercial web offset printing press. Polar show off the POLAR Compucut, a system for computer-assisted, external generation of cutting programs with automatic transfer to the cutting machine.

The Xerox Docutech, launched in 1990, combines a 135 page-per-minute black & white xerographic print engine with a scanner and finisher modules. It is arguably the first affordable print-on-demand publishing system.

In 1992 Australia is the first country to use polymer

banknotes for general circulation.

Digital printing takes off in 1993 with the introduction of the Indigo E-Print 100(shown below) and Xeikon DCP-1.

Offset presses still evolve incrementally. Two prime examples are the introduction of the KBA Cortina, a waterless web press for newspapers and semi-commercials, in 2000 and that of the giant Goss Sunday 5000, the world’s first 96-page web press, in 2009.

Bigger changes happen in digital printing with machines that evolve as fast as the companies that produce them. Take the NexPress for example. It is initially a joint development from Heidelberg and Kodak, later taken over completely by Kodak.

One of the bigger players in the market is HP, especially after its acquisition of Indigo in 2001. Other big players in the market are Konica Minolta with the Bizhub digital presses and Canon with its Imagepress range. Part of Canon’s growth is through its acquisition of Océ in 2009.

One area of the market that evolves quickly is that of large format inkjet presses for the sign & display market. Inkjet technology also starts making inroads in the packaging industry. At the 2016 edition of drupa the EFI Nozomi C18000, HP PageWide C500 and Durst Rho 130 SPC (shown below) are all presses optimized for printing on corrugated packaging board.

Source: https://www.prepressure.com/printing/history